The Brain of the Beholder

Jun 15

Over ten years ago I attended a Vipassana meditation course at Blackheath in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. This was an intensive ten-day course, free of charge (donations are of course welcome), where you could learn the art of meditation, and be introduced to some basic Buddhist teachings.

Over ten years ago I attended a Vipassana meditation course at Blackheath in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. This was an intensive ten-day course, free of charge (donations are of course welcome), where you could learn the art of meditation, and be introduced to some basic Buddhist teachings.

There were some rules however, most notable among them being that you could not talk to, communicate in any way with—or even meet eyes with—anyone else on the course, a discipline known as ‘noble silence’. Simple vegetarian meals were provided, along with basic accommodation. And you had to rise at 4am and meditate about eleven hours a day.

Needless to say, this was hard. At the end of each day there was a short period where you watched, as a group, a video featuring the main teacher of the technique; and at this times I was sharply aware of how easy it would be to fall into a cult mentality; deprived of the normal stimulations of everyday life, one can get obsessive about a wise word and a kind face. As far as I know however, a Vipassana course is a benign and useful way for those wishing to experience a somewhat extreme, but extremely educational, introduction to the beneficial discipline of meditation.

For most of the ten days, I found this discipline extremely difficult, and often physically painful—sitting still for hour upon hour is not an easy thing to do. The mental discipline required was even more difficult. I won’t go into it in detail, but the technique basically involves an awareness of breathing, and a focussing of your mental awareness on small areas of your body, until finally you achieve an uninterrupted ‘flow’ of awareness up and down your body.

After about eight days, I had what you might call an epiphany. Suddenly, I achieved the ability to focus my concentration from the top of my head to the tips of my toes and back again in a smooth flow; a flow that I can only describe as a ‘golden light’ washing up and down my body. After days of struggle, there were no distractions, no intruding thoughts, only total and utter concentration on this one flow of awareness. It was one of the most extraordinary sensations I’ve experienced in my entire life.

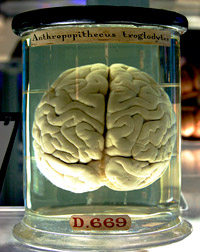

So why am I telling you all this? Because it opened my eyes. Not in a ‘I’ve discovered the key to the universe’ kind of way, but in ‘so this explains it’ kind of way. To many people, I imagine, such an experience would have been a religious or spiritually revelatory one. To me, it demonstrated a fundamental truth, and here it is: the brain is capable of the most incredible things, and it requires an intelligent, informed use of the brain to interpret its input.

I was reminded of this entire experience recently when I watched Derren Brown’s television special, ‘The System’. For those of you who haven’t seen it, it’s a 2008 program where Brown, a popular British sceptic and illusionist, presented a ‘system’ for winning on horses that seemed absolutely infallible to what appeared to be a random member of the public. It is only in the later stages of the program that it is revealed that this person is in fact only one of almost 8,000 people that Brown had introduced to his ‘system’, and that by playing the laws of probability, he had focussed on the one person from that entire group who had won five times in a row—and easily convinced her to get horribly in debt because she believed the system was infallible.

As Brown explained, people believe things because they are imprisoned by their own unempirical viewpoint. They don’t think beyond ‘it worked for me’: they accept anecdotal evidence. We all operate within a subjective frame of reference that makes us, as human beings, incredibly susceptible to being conned or avoiding the hard work that is involved in researching the truth. We are all—to paraphrase what P.T. Barnum so memorably said—the suckers that are born every minute.

I’ve often thought about the experience I had on the Vipassana course, and how it could be interpreted. Some would choose to interpret it as a spiritual experience, or even a religious one. Some would choose to dedicate their life to its further exploration. Some would ascribe it to lack of sleep and human contact. Some would recognise similar experiences from drug use. To me, it was a unique insight into the human brain, and what it is capable of—even after just ten days of intensive training. But most would need to assign some kind of meaning to the experience, because that is the thing that humans have always needed to do. We assign meaning to coincidences, despite the bare facts of probability, and we imagine magical forces instead of exploring natural ones. We cling to the easy explanation instead of trying to find the difficult truth. We believe what we want to believe.

We’re a funny old lot. We bet on the horses, fill out lottery coupons, pray at altars, swallow the homepopathy remedies, and all the while we say it works for us. But instead, we should be using the one thing that is the source of all our experience—our brains. They are capable of so much.

Jun 16, 2011 @ 08:56:35

You know that old myth about people only using 10% of their brains? I’ve come to believe it’s actually true. It helps explain the vast proportion of idiots.